This post is about the course BIOS1100 - Introduction to Computational Modelling in the Biosciences, that I have taught at the University of Oslo, Norway since 2017. I describe why and how we incorporated participatory live coding (students ‘coding-along’ with an instructor) into the teaching, and what effects this technique has had on first-year bioscience students learning programming in Python.

Background

From 2017, the Biosciences bachelor study program have started to incorporate Computing in Science Education (CSE) into the different subjects. As part of this effort, I develop and teach a new semester-long course “Introduction to Computational Modelling for the Biosciences”. The course teaches first-semester students Python programming and basic mathematical modelling. BIOS1100 is not a pure programming course, Python is taught so students can used it to implement simple mathematical models to address relevant biological questions.

In two earlier blog posts, I explained the rationale behind the course and how the first edition went. In that latter post, I concluded that I needed to use Participatory Live Coding to teach students the basics of Python programming.

What is Participatory live coding

Participatory live coding is a technique where a teacher or instructor writes and narrates code out loud as they teach, and invites learners to join them by writing and executing the same code - they ‘code-along’ with the instructor. Benefits of participatory live coding are that it slows the instructor down, allows for making the thought process of programming explicit, activates the learners and shows them how to diagnose and correct mistakes.

Participatory live coding is the main teaching method in workshops organised by the global non-profit called The Carpentries, the umbrella organisation for Software Carpentry, Data Carpentry and Library Carpentry. As an active Carpentries instructor, I use this technique when teaching, for example, programming, the Unix shell or the use of the version control tool git.

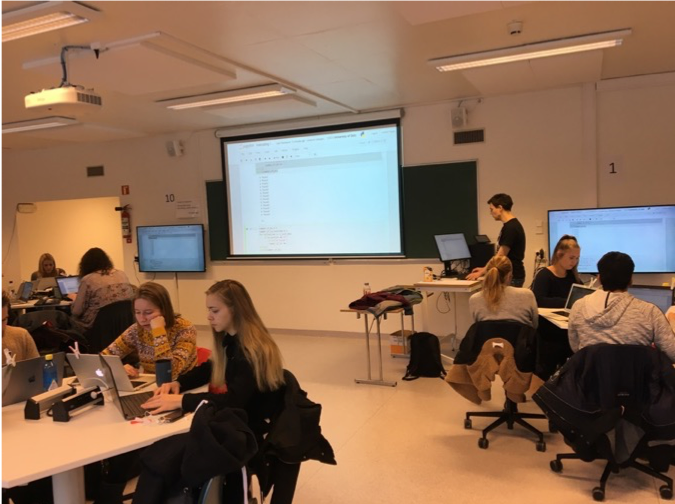

Participatory live coding and BIOS1100

In the first edition of my BIOS1100 course, I initially did not want to use the technique as I thought it wouldn’t scale up to the 60 or 200 students in the room during group sessions, or lectures, respectively. But I ended up using participatory live coding in the latter part of the course to help students that struggled learning the programming part of the course. Based on the positive feedback from the students I then decided to implement participatory live coding as the main technique for teaching elementary Python concepts in BIOS1100 from then on.

The challenge

How to teach using participatory live coding to large groups of students? Carpentries workshops have usually no more than 30 participants and a healthy helper-to-participant ratio (1 to 10 or better). In BIOS1100, students meet in groups of up to 60, or in lectures up to 200. An important aspect of live coding is keeping all learners engaged and not leaving anyone behind because they run into a problem. The challenge for BIOS1100 was how to make sure one student getting stuck not delaying all the others. Also, with a lecture and four four-hour group sessions each week, doing all the live coding myself would constitute an enormous workload - teaching in itself is tiring, and teaching using participatory live coding usually even more so.

The solution

The most important thing I did was to train several teaching assistants (graduate students with teaching duty as part of their PhD) in how to deliver a lesson using participatory live coding. I asked each one to prepare for this by assigning them the relevant parts of the Carpentries instructor training materials. I then had each of them do a live practice session in front of the others and myself, where they gave each other feedback.

I also spent a lot of time carefully preparing lesson materials for the live coding sessions in advance. Teaching at this levels is done in Norwegian, so I (mostly) wrote this material in that language.

We used the University of Oslo’s JupyterHub, a cloud-based service enabling students to use Jupyter Notebooks, with any necessary packages pre-installed and an easy way for instructors to distrubute files to all students. This common infrastrucure meant no installation issues on student’s machine, and helped limit the kind of technical problems learners often run into.

The results

In the 2018 edition of BIOS1100, participatory live coding was used during the obligatory 4-hour group sessions. Students loved it! Teaching assistants reported back to me that they students had a much better foundation in basic Python. However, we used so much of the four hours available for each groups session for live coding that there was too little time left for the students to work on exercises on their own with the help of the teaching assistants.

For the 2019 edition I thus decided to use weekly 2-hour non-obligatory sessions with participatory live coding sessions for the foundational Python. These sessions were focussed on the coding-along part, with deliberately little time for exercises. In group sessions, live coding was still used for worked examples, to demonstrate things and to explain material that the students struggled with. This left enough time, usually at least 2 hours, for working-on-your-own on exercises in the classroom (discussing with each other and/or the teaching assistants).

The experience from the 2019 model was that a number of students that should have gone to the participatory live coding sessions didn’t attend them, as these were voluntary. But we kept the benefit of the students that did participate learning the material very well.

Surprisingly, having students fall behind was never a big issue. Teaching assistants present during the live coding sessions reported usually having very little to do in terms of helping students getting unstuck. This may have been due to the fact that everyone, student as well as instructor, used the same Jupyter environment. Students were otherwise very good asking the instructor doing the live coding for help when they lost track.

Although I tried it out a few times, so far I have decided against doing participatory live coding during lectures with all students together. It happened too easy that one or two students miss a vital piece of information and get stuck, but didn’t notify me and thus missed a section of the live coding.

Why does it work?

I have often asked myself what it is about the code-along style of teaching that makes it so successful for teaching programming and similar subjects to novices. I think part of the answer has to do with motivation and mindset. My students probably did not choose the Bioscience program at the University of Oslo because they wanted to learn Python programming. Yet, this is what they are taught from the very first semester. As for the people signing up for Carpentries workshops, many of them figured out that their research or career would benefit from learning computational skills. However, they also may think that learning to program is a scary thing and ‘not for them’.

The technique of participatory live coding is carefully guiding the learner through the early stages of learning programming. It is almost as if the instructor is hand-holding the learner and thereby lowering the barrier to get started. I have had BISO1100 students give me feedback that they overcame their fear of programming already after one live coding session. It suddenly wasn’t scary anymore! Proper research needs to be done to confirm these suspicions, but my hypothesis would be that learners with low confidence in their ability to learn programming at the start of a course benefit from the participatory live coding approach in that it helps them obtain a growth mindset towards learning programming.

The future

I may in the future may make the participatory live coding sessions obligatory, with exemptions for students with sufficient Python knowledge. Until then, I want to do a better job at ‘selling’ the sessions, ensuring that students who need them actually attend them.

Although we won’t be doing participatory live coding in lectures, I do want to experiment with non-participatory live coding, i.e. demonstrations and worked examples during those times all students are together with a teacher. The students like seeing their teachers program and there is value in spending time on going over exercises from the previous week or demonstrate code that helps address misconceptions.

Finally, I hope to convince others aiming to teach programming to audiences normally not having it as part of their studies (humanities! social sciences!) to adopt this method of teaching, at least in the beginning.

I am now confident that I have found a teaching model for BIOS1100, using participatory live coding, that enables us to focus on applying programming to what the BIOS1100 course really is about: an introduction to computational modelling of biological problems!