I am very much interested in Artificial Intelligence (AI), both in general, and in what it means for (higher) education. My focus is mostly on Generative AI, such as Large Language Models (LLMs), Image generation etc. I am mostly trying out how much I can get done using tools that my university has enabled me to use. These include the University of Oslo’s own wrapper around OpenAI’s ChatGPT (gpt.uio.no), and Google’s NotebookLM. I also have obtained API access to OpenAI’s GPT models, provided by the university through the Microsoft Azure platform. I use this to write code (with the help of the Roocode plugin for Visual Studio Code). I also use commercial platforms (Google Gemini, Google AI search, Perplexity, ChatGPT) but so far have no paid subscription to any of them1.

I hope to occasionally post some of my experiences, findings and opinions on this blog. Here is the first post!

An important aspect to understand when working with LLMs is that at a basic level, they are next-token predictors. A token here means a word, or part of a word. This means that given a set of tokens, for example, your question (prompt), LLMs use their model to predict possible next tokens, and choose one of the most likely ones. Based on all previous tokens, and the one just chosen, the model is then used to predict the next ones and choose one of these. There is some stochasticity here, so asking the same model the same question twice may in fact yield slightly different results.

Still, these next-token predictors turn out to be generating surprisingly well-written sentences. This is what makes them so useful.

Hallucinations - LLMs dreaming up things

Sometimes the model will go astray, especially if it is asked about something that is not in its training data (or that it cannot look up elsewhere). The result is plausible-looking wording that may be complete nonsense. This is what is usually called hallucinations.

In the spirit of the subtitle of this post: I think the word ‘hallucination’ is a misnomer. Hallucination is defined on Wikipedia as

[…] a perception in the absence of an external context stimulus that has the compelling sense of reality.

When hallucinating, one may see something (a perception) that isn’t really there.

LLMs generating plausible but nonsense text don’t perceive anything. Therefore, this phenomenon I’d rather call ‘Dreaming up things’, or ‘confabulation’. That latter term is defined, again using Wikipedia, as

[…] a memory error consisting of the production of fabricated, distorted, or misinterpreted memories about oneself or the world. […] Confabulation occurs when individuals mistakenly recall false information, without intending to deceive.

That last part, ‘without intending to deceive’ is important (if you’ll allow me a bit of anthropomorphism, as an LLM cannot really have intention - more on that below). Unfortunately, we are already stuck with the word hallucination.

Simulated Intelligence

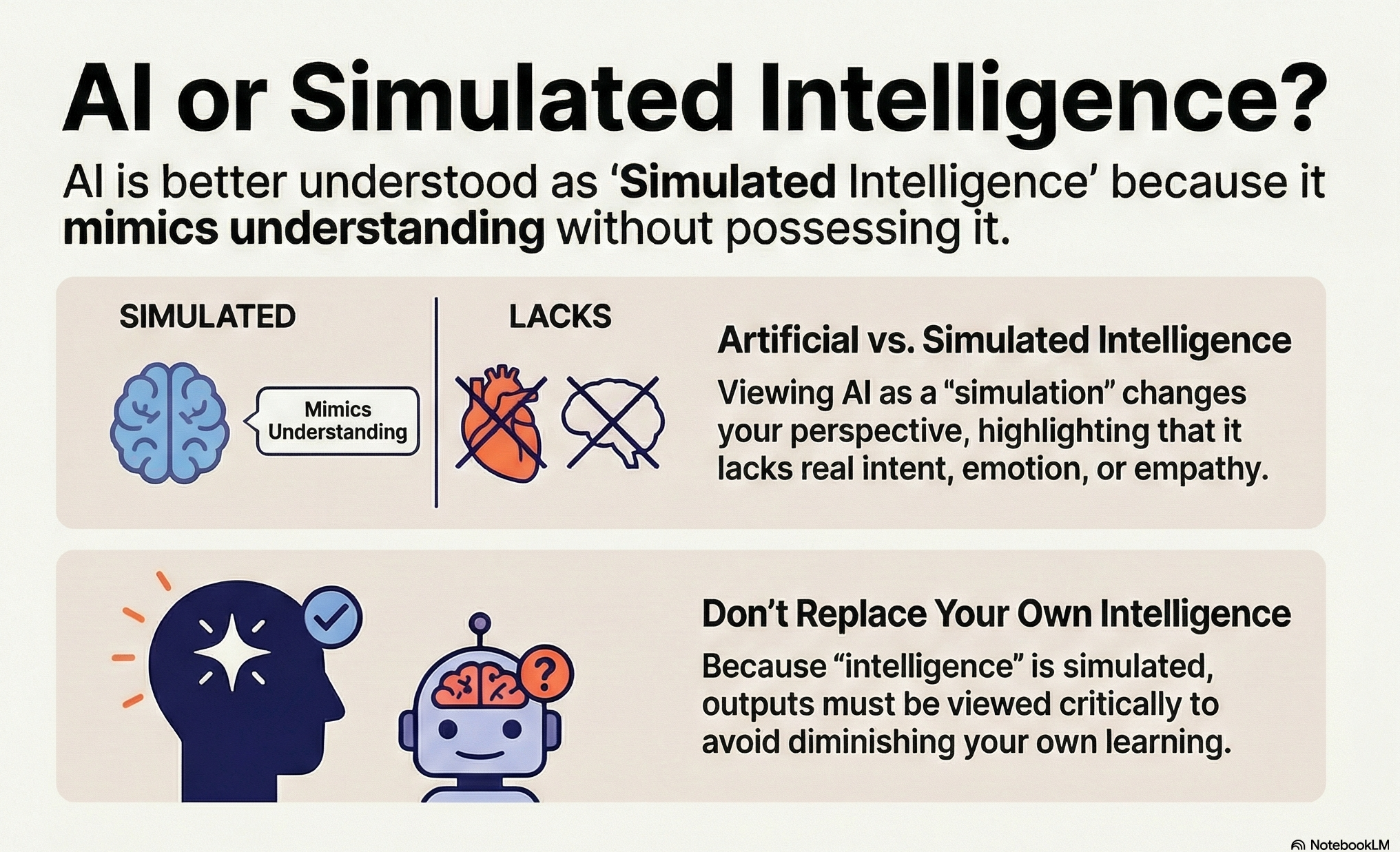

Modified infographic generated by NotebookLM.

Modified infographic generated by NotebookLM.

My main point with this post is that also the term ‘Artificial Intelligence’ could be said to be misleading. Writing this post was inspired by reading the White Paper by Tom Chatfield entitled “AI and the Future of Pedagogy” 2. This White Paper makes many valuable points. Here, I’d like to focus on one of them.

I quote:

Within the space of a few years, it has become possible to simulate knowledge and understanding of almost any topic while possessing neither.

The use of the word “simulate” really resonated with me. If we consider the output of LLMs to be ‘Simulated Intelligence’, rather than “Artificial Intelligence”, that changes our perspective. It may look intelligent, but it is not real intelligence, it is simulated. Chatfield also writes about LLM’s ability to “simulate social interactions”. And “Modern generative AIs are all too adept at simulating emotion, empathy and interest.”

I think using this term may help a lot with interpreting the outputs from LLMs, and making use of them. If the ‘intelligence’ is simulated, one needs to look at it critically, because it may have weaknesses. It should not be used to replace one’s own intelligence. Intelligence simulated by a machine cannot have intentions. Looking at it this way may also help students apply it carefully so as to not diminish their learning.

Tom Chatfield is not the only, or even first one to use this word. A ‘quick’ Deep Research query with Gemini (through Google AI Studio) or Perplexity yields several others that have explicitly suggested using the term “Simulated Intelligence”3. But for me, this was the first time I came across this term.

I hope this may be a useful perspective for others as well.

Comments on this post are welcome on LinkedIn.

Footnotes

Except for the image, no generative artificial intelligence tools were used in the writring of this blogpost.↩︎

Chatfield, T (2025). AI and the future of pedagogy (White Paper). London: Sage. doi: 10.4135/wp520172 https://www.sagepub.com/explore-our-content/white-papers/2025/11/03/ai-and-the-future-of-pedagogy↩︎

A good example is David Sherwood, “Artificial Intelligence or Simulated Intelligence?” https://cogscisol.com/artificial-intelligence-or-simulated-intelligence/.↩︎